The ups and downs of a rangers family life on a game ranch in Africa

Travelling on gravel roads during the rainy season where wildlife roams free.

It has been raining for days. The gravel roads on this African game ranch have turned to mud and animals roam freely. Jenny travels through challenging conditions to collect her children from boarding school. The return journey has its problems – trapped, alone without communication.

You can read all of my short stories here on my website, just by becoming a subscriber – it’s free!

It had been raining without a break for three days, and I had cabin fever. The drought had broken after years of waiting and watching the agony of wild animals dying from starvation. The only creatures thriving were the carnivores—lions, cheetahs, wild dogs, and hyenas—meat-eaters with fat bellies, gorging on the flesh of animals too weak to outrun them.

My husband Burt and I lived at Pachikomon {“On the hill” in Shona}, a conservation wildlife reserve in the south of Zimbabwe. After many years of a severe drought, life-giving rain had arrived and continued to pour from heavy grey clouds. The muddy roads and steadily rising rivers were a concern when driving to and from the homestead. I had no choice; I would leave the house at dawn and travel to Bulawayo to collect our children, Rosie and Tommy, from boarding school.

Burt had received a radio message from his poaching team and was hurriedly dressing.

‘Poachers have cut the game fence on the Eastern border. Our trackers have picked up their trail, so let’s hope we get to them before they kill any rhino.’ He slung a rifle over his shoulder. ‘I’m taking some men to repair the fence; it won’t be much fun in this weather, but I should be back home before you return this evening, Jen.’ He bent to kiss me. ‘Be careful on these roads; they can be treacherous, and make sure you get home before dark.’

The African wildlife in the Pachikomo conservation reserve were protected by a two-meter-high game fence, a crucial barrier consisting of poles and galvanized fencing stretching around the perimeter. The animals roamed freely, living in harmony with those who came to view or photograph them. Armed rangers patrolled the fence line and radioed back to a support team if there was a problem – often it was poachers.

I swallowed the last sip of tea. ‘I’d better also get a move on. I’ll message you via Sandra and Pete, when we’re about three-quarters of an hour from home. Let them know if the bridge goes under water, then we’ll spend the night with them.’ I was acutely aware of the need for caution on these treacherous roads, especially with the weather conditions worsening.

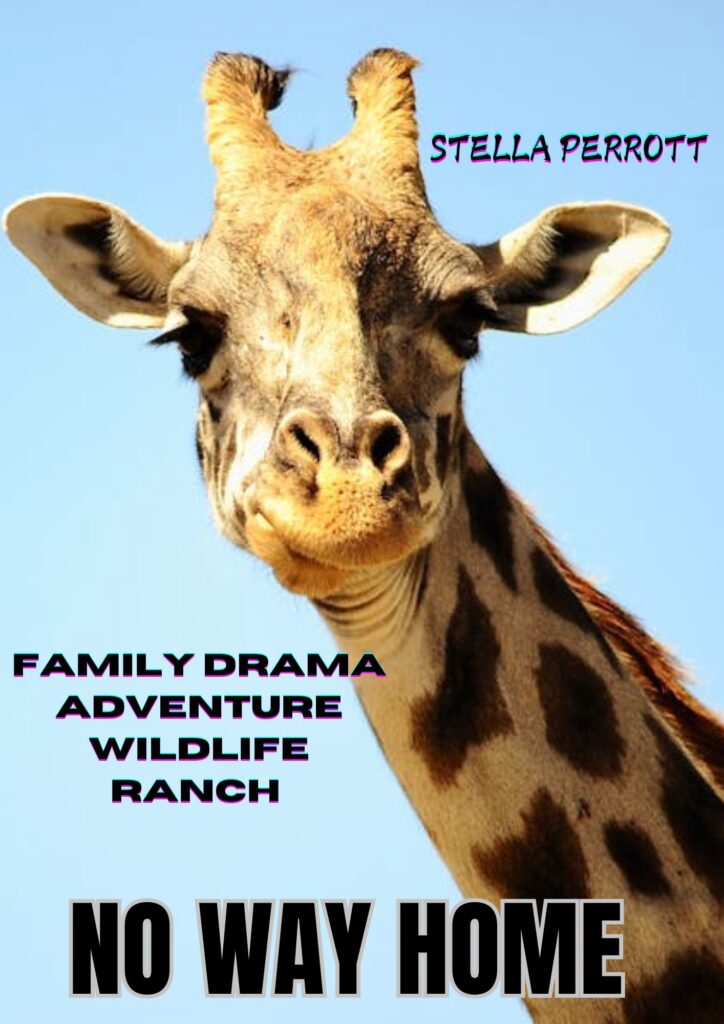

The 4WD tyres ploughed through thick mud as I drove between sparse mopane trees thickening into dense woodland. Elephant activity was evident by the large dung droppings and freshly snapped branches. As I progressed into sandy soil, there was a change in vegetation with tall acacia trees lining the road, sharp thorns and sweet leaves; a great favourite with giraffes, their long slim tongues adeptly avoided the prickly barbs. On leaving the reserve, I gripped the steering wheel as the vehicle bounced over a steel grid indicating I was leaving the reserve.

‘Phew, what a relief,’ I sighed as the Land Cruiser tyres hit the smooth surface of the tarmac road. The windscreen wipers swished back and forth during the two-hour journey to Bulawayo. Once there, I loaded supplies into the canopy of the dual cab before driving to Tommy’s school. Our son didn’t enjoy school, and the anticipation of a three-week holiday at home in the bush had him bursting with excitement.

‘Hiya, Mum,’ He hugged me, then threw his case into the back of the vehicle. ‘Let’s go, Mum. Let’s go,‘ he didn’t try to disguise his eagerness to get out of there. I smiled, recalling Tommy’s reaction when we first told him he was going to boarding school.

‘Why do I have to go away to boarding school?’ he asked.

Burt had explained, ‘Because you need an education, my boy. You’ll have to earn a living to support your family when you’re a grown-up.’

‘I don’t want a family. I’m staying here with you forever. I’ll chop firewood and sell it on the side of the road and,’ he quickly thought of another reason. ‘I’ll grow my own food and drink water from the river.‘ My heart had gone out to my little boy. He was a proper bushman, and the thought of earning a living by any other means was foreign to him.

Back in the moment, with Tommy bouncing in the back seat, I drove to the girls’ high school to collect fourteen-year-old Rosie, who scowled as she walked towards the Land Cruiser.

‘Why do you always collect Tommy first?’ she complained without greeting me, then slammed the door.

‘Well, hello to you too, Rosie.’ I was annoyed that she’d shrugged off my attempt to hug her. ‘I collected you first last time. Remember? You kept me waiting because you like to say goodbye to your friends at the end of term. So, this time, I gave you plenty of time to say your goodbyes.’

‘They all went home long ago. I’ve been sitting here by myself for ages.’

‘Well, you can’t have it both ways.’ I took a deep breath. I had to remind myself that she was a teenager.

***

It was still raining steadily an hour later as we travelled homeward along the tarred road through scraggy savannah bushland, passing the occasional African village with clusters of varying-sized circular thatched houses. A sudden loud bang left me struggling to control the heavily laden Land Cruiser.

‘Oh hell! Hold on,’ I shouted as we veered into oncoming traffic. I used all my strength to force the vehicle back onto the left side of the road while resisting the temptation to slam on the brakes. I was worried about rolling the car. After I slowed down, the dual cab limped into a layby and eventually stopped. I closed my eyes and rested my head on the steering wheel, my heart pounding in my ears.

‘Dear heavens, thank you, Lord, for providing a safe place to pull over.’ I reached over to Rosie. ‘Are you okay, Sweetie?’ She snuggled into my arms, trembling.

‘That was so scary, Mum.’

‘It’s okay, my girl. We’re safe now.’ I smoothed her beautiful, long brown hair. Suddenly, she pulled away, remembering she was angry with me for collecting her brother first. I turned to check on Tommy. His eyes glowed with excitement. He had enjoyed the whole experience.

‘Geesh, Mum. We nearly crashed.’ He found the fun side of every occasion. I looked up as a vehicle pulled in next to us. It was our neighbour Pete. I opened the window.

‘Do you need a hand with that tyre, young lady?’ He asked.

‘Thanks for stopping, Pete. I appreciate the help, especially in this rain.’ I reached for my raincoat and told Rosie and Tommy to stay in the car while we changed the tyre. With Pete’s help, we were soon back on the road. He was travelling into Bulawayo but assured us that Sandra was home.

Pete and his wife Sandra were our closest neighbours, some 60 kilometres away. Our homestead on the Pachikomo ranch was out of mobile phone range, and there was no telephone. It was pointless having telephone poles when elephants knocked them down faster than they could be replaced. The only means of contact with the outside world was by radio. Burt and I had lived on the ranch in this remote area for twelve years. We loved the rural, unsophisticated lifestyle we lived.

***

As promised, I phoned Sandra when we were fifteen minutes before we left the sealed road.

‘Hi Sandy, please radio Burt to check if we can still cross the bridge. Tell him I’m running late, but I’ll try to get there before dark.’

The rain had eased to a drizzle when Sandra called back. ‘Burt’s checked the bridge, and the water’s lapping the sides, but you should get across okay. He’ll wait for you at the bridge.’

The light faded as I drove across the grid onto the dirt road inside the reserve. We were twenty-five minutes from home, and there was no communication along this short stretch of road, but what could go wrong? I switched the headlights onto the full beam and slowed down, allowing for the muddy conditions. Bumping into a wild animal was an added danger, especially when they stood in the middle of the road. Water lapped over a narrow bridge, but I took a chance and ploughed through the water, then crawled behind a pair of giraffes strolling in front of us. I breathed a sense of relief and picked up speed when the lanky legs eventually veered off into the bush.

We were making good time when a flash of lightning frightened Rosie. She screamed, distracting me. I was already stressed and didn’t need the extra adrenaline rush.

‘Keep it down, Rosie. I’m battling to keep the wheels on the road without you adding to the drama with your screaming.’ The windscreen wipers battled against sheets of pelting rain. ‘I need my wits about me. I can hardly see a thing,’

‘Mum, I’m petrified. Please hurry.’ Rosie urged.

‘I can’t go any faster; you know how treacherous these roads aaar..!’ I pulled hard to the right, missing an enormous elephant mb millimetres. We skidded through thick mud, my foot on the brake as we bounced down an embankment, whizzing through trees before we came to a halt in a shallow ditch.

…That’s all you can read without being a subscriber! But if you’ve read this far, it’s obvious you want to read more.

Just pop back up to the top of the page and sign up – it’s FREE!

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

If you’d like to read this story as a PDF, MOBI, or ePub (so you can read in Preview, Apple Books or Kindle formats), you can access it via https://extras.stellaperrott.net/free-story-no-way-home